Understanding Derivatives: Risks and Rewards

In finance, a derivative is a contract whose value is derived from the performance of an underlying entity, such as an asset, index, or interest rate. This underlying entity is typically referred to as the ‘underlying’. Derivatives can be used for a variety of purposes: to hedge against price movements, to speculate on market directions, or to access otherwise difficult-to-trade assets or markets.

Common types of derivatives include futures, forwards, options, swaps, and more complex instruments such as credit default swaps (CDSs) and synthetic collateralised debt obligations (CDOs). These contracts are either traded over-the-counter (OTC) or on exchanges like ICE Futures Europe (formerly LIFFE) and Turquoise (part of the London Stock Exchange Group). Following the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, regulators increased efforts to push derivatives trading onto exchanges to improve transparency and reduce systemic risk (Duffie and Zhu 2011).

Futures and Forwards

A future is a standardised, exchange-traded forward contract. It is a legally binding agreement to buy or sell an asset at a specific future date, at a price agreed upon when the contract is initiated. These contracts impose open-ended obligations on both parties:

Long position: The buyer agrees to purchase the underlying asset in the future, hoping prices will rise.

Short position: The seller agrees to deliver the underlying asset in the future, hoping prices will fall.

Each party must honour their contractual obligations until expiry or until the position is closed.

Whilst similar, forwards are non-standardised, OTC agreements. They are customised between counterparties and often used by institutions to tailor risk exposure. Futures, by contrast, benefit from the transparency and risk mitigation provided by clearing houses.

What determines futures prices?

The price of a futures contract reflects not only expected future spot prices (price at which an asset can be bought or sold for immediate delivery), but also other factors such as the risk-free rate, storage costs, and any income generated from holding the asset.

For income-generating assets like dividend-paying shares, futures prices tend to be lower than the spot price, because the holder of the futures contract misses out on interim income.

For cost-incurring assets like livestock, futures prices tend to be higher than spot prices, as the contract buyer avoids ongoing costs like feed.

This price differential helps compensate the short seller who bears those income or cost implications in real time.

Options: Calls and Puts

Options are powerful tools that confer the right, but not the obligation, to transact in an underlying asset at a predetermined strike price on or before expiry.

A call option gives the holder the right to buy the asset.

A put option gives the holder the right to sell the asset.

The buyer pays a premium for this right, whilst the seller assumes the obligation to fulfil the contract terms if the buyer exercises the option.

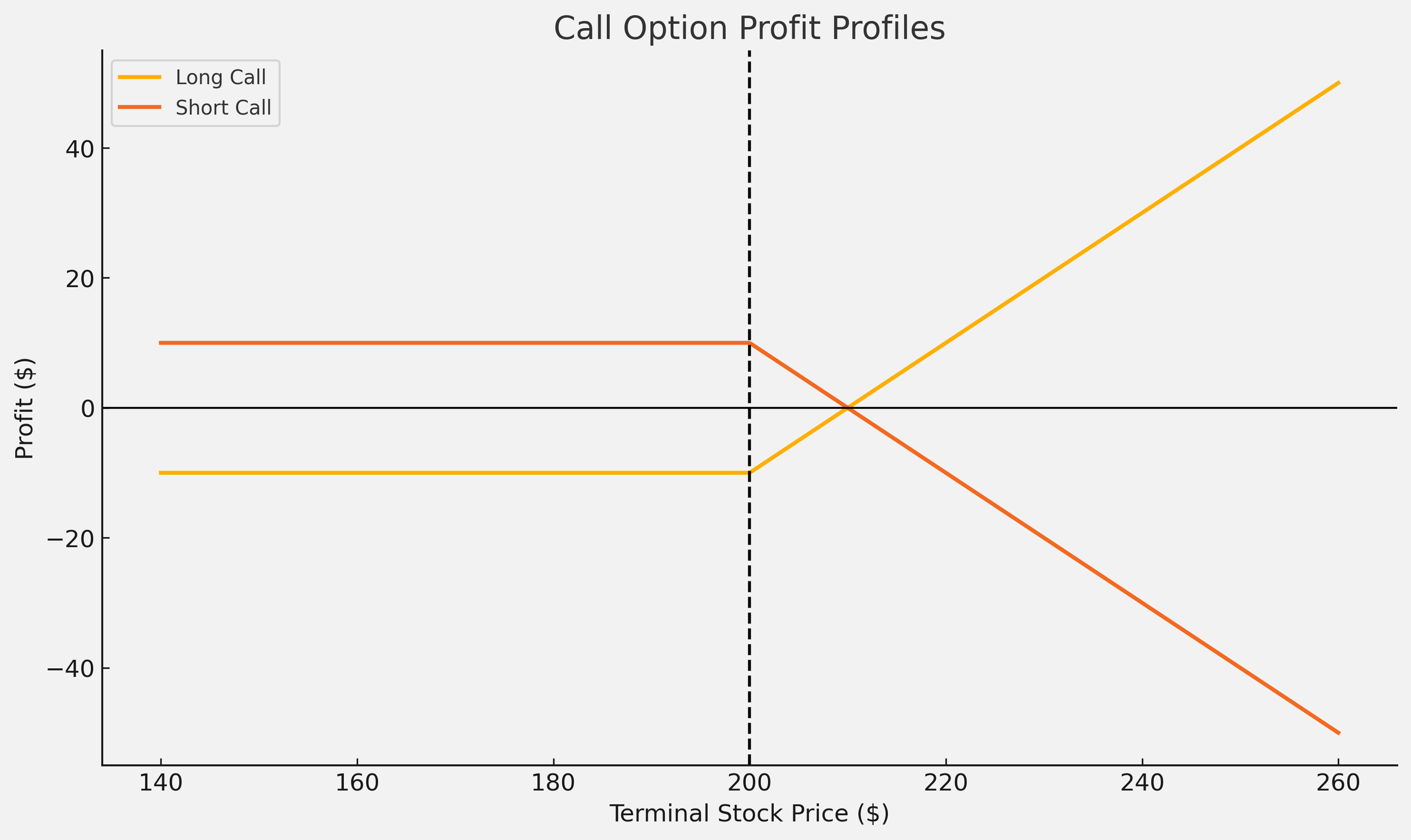

Call Options

Call options benefit from upward price movements in the underlying asset. They offer unlimited upside with limited downside (the premium paid).

Example: Suppose you believe Nvidia shares will rise from $10 to $20. You purchase a call option for $0.50 with a strike price of $13. If Nvidia reaches $20, you can buy it at $13 and profit $6.50, netting a 1300% return on your initial $0.50 outlay.

For the seller (writer) of the call option, the risk is substantial. If Nvidia reaches $20, they must provide the shares at $13, potentially suffering large losses. Their maximum gain is limited to the premium received ($0.50).

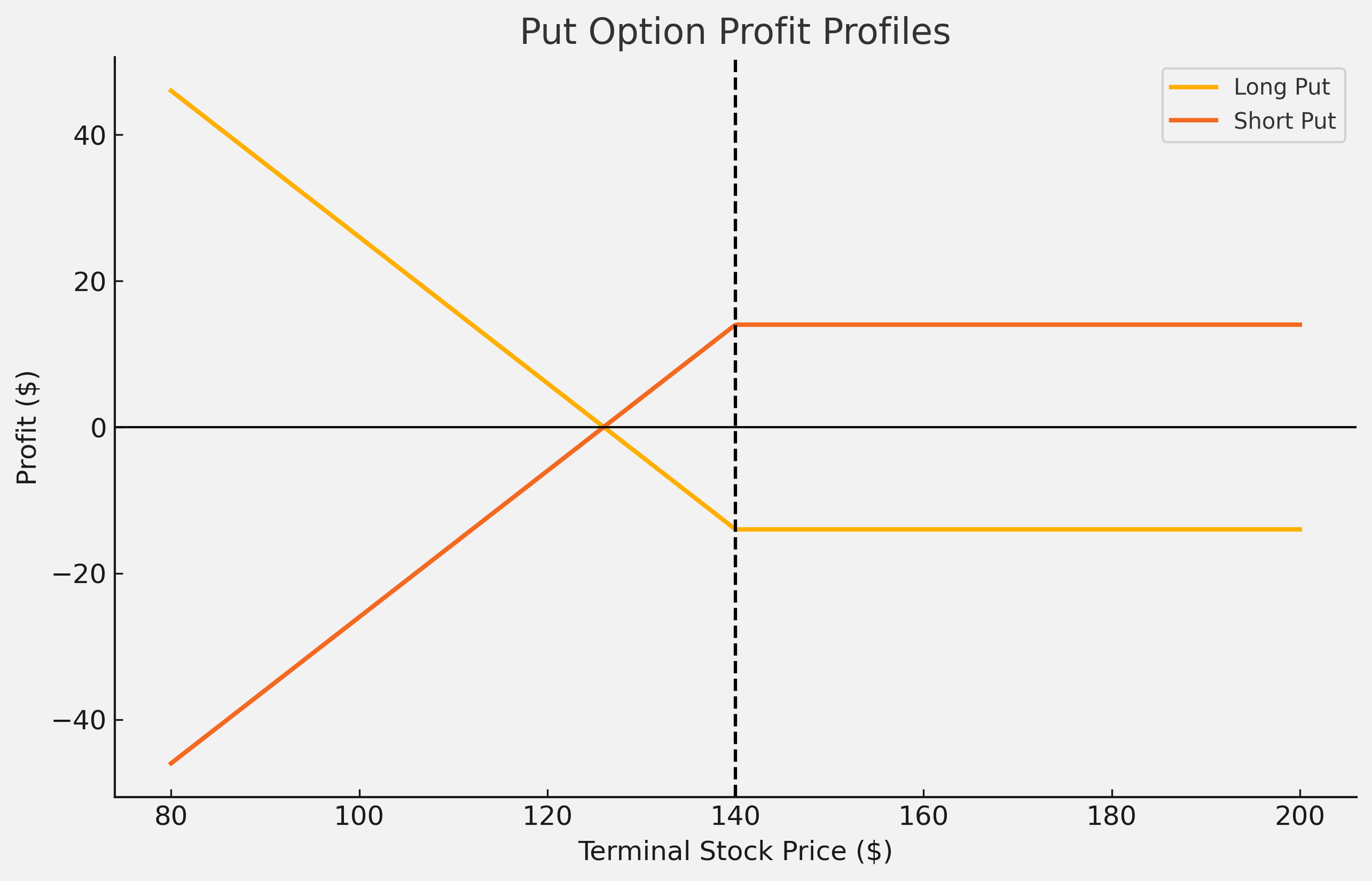

Put Options

Put options rise in value when the underlying asset declines. Long puts are often used to hedge against falling markets or to speculate on downward moves.

Example: You believe Apple shares will fall from $100 to $50. You buy a put option for $2 with a strike price of $75. If Apple reaches $50, you can sell at $75, netting $23 in profit on a $2 investment—a 1150% return.

The seller of a put option, however, faces the risk of being forced to buy the asset at an above-market price, again for limited gain (the option premium of $2) and potentially substantial loss.

Note: A protective put is a popular risk-management strategy where investors hold a long position in a stock whilst purchasing a put option to hedge downside risk—similar to buying insurance (Black and Scholes 1973).

American vs European Options

American options and European options differ primarily in when they can be exercised. A European option can only be exercised at expiry, meaning the holder must wait until the contract’s maturity date to realise any payoff. In contrast, an American option can be exercised at any time up to and including expiry, offering greater flexibility. This early exercise feature can be valuable, especially for dividend-paying stocks (in the case of call options) or when deep in-the-money puts offer a strategic advantage before expiry. As a result, American options are typically worth at least as much as their European counterparts, all else equal. However, most index options are European-style, whilst stock options tend to be American-style.

Figure 1. Long and short European call options with a $200 strike and $10 premium. Profit for both profiles factors in the option premium paid/ received.

Figure 2. Long and short European put options with a $140 strike and $14 premium. Profit for both profiles factors in the option premium paid/ received.

How Options Are Covered in the Market

When someone buys a call or put option, they acquire a right, not an obligation. But someone on the other side of that trade, the seller (writer), must be prepared to fulfil that right if it is exercised. This leads to an important concept: options must be ‘covered’ in the market, meaning that the seller must post sufficient margin or own the underlying asset to meet their potential obligation.

Call Options

If you sell (write) a call option, you are giving someone else the right to buy an asset from you at a fixed price (the strike price).

If the price of the asset rises above the strike, the buyer will exercise the option and you, the seller, must deliver the asset.

There are two ways to be prepared:

Covered call: You already own the asset and can deliver it.

Naked (uncovered) call: You do not own the asset and will have to buy it on the open market, potentially at a much higher price, exposing you to unlimited risk.

Exchanges and brokers require margin for uncovered calls to protect against this risk.

Put Options

If you sell (write) a put option, you are giving someone else the right to sell you an asset at the strike price.

If the asset’s price falls below the strike, the buyer will exercise the option and you must buy the asset, even if it has plunged in value.

To cover this obligation, the seller must either:

Hold enough cash or liquid assets to purchase the underlying if exercised.

Post margin with the clearing house or broker to cover the potential shortfall.

Like call options, naked puts are risky and heavily regulated.

Writing a Call Option (Naked Call)

Maximum loss: Unlimited

Why? If the stock price rises far above the strike, you must sell the stock at the strike price, even if the market price skyrockets. Since there’s no upper bound to stock prices, your potential loss is theoretically infinite.

Example: You write a call with a $100 strike and no stock position. If the stock hits $300, your loss is $200 per share minus the premium received.

Writing a Put Option (Naked Put)

Maximum loss: Capped

Why? The worst-case scenario is the stock going to zero, and you’re obligated to buy it at the strike price. That gives a maximum loss of strike price minus the premium.

Example: You write a put with a $100 strike. If the stock falls to $0, you must buy it for $100, losing $100 per share, less the option premium received.

Exchange-Mandated Coverage

Options traded on regulated exchanges (e.g. the Chicago Board Options Exchange or ICE Futures Europe) are subject to strict margin and collateral requirements. These ensure that all obligations can be honoured and reduce the risk of counterparty default.

Clearing houses like Options Clearing Corporation (OCC) act as intermediaries and enforce this coverage through:

Initial margin: A deposit required to open a position

Maintenance margin: A minimum equity level that must be maintained

Daily marking to market: Unrealised gains/losses are settled daily, reducing credit risk

In essence, these rules mean that for every option contract open in the market, the obligations on both sides, buyers and sellers, are backed by capital. This ensures the integrity of the derivatives market and protects all participants.

Swaps and Structured Products

Swaps are OTC contracts in which two parties exchange cash flows. A common example is an interest rate swap, where one party exchanges a fixed interest rate for a floating rate. Swaps are vital for institutions managing interest rate exposure, currency risk, or commodity price fluctuations.

Structured products, including with-profit funds and Yield Enhancement Products (YEPs), bundle derivatives with traditional investments. These often offer capital protection or enhanced income but come with embedded complexity and risk.

Contracts for Difference (CFDs) and Spread Bets

CFDs and spread bets are leveraged instruments that allow traders to speculate on price movements without owning the underlying asset. Whilst they offer high upside, they also magnify losses. These products are especially popular among retail traders, though many regulators have placed limits on their promotion due to the risk involved.

Short Selling and Derivatives

Short selling is a trading strategy that allows investors to profit from a decline in the price of a security. It involves borrowing shares from a broker and immediately selling them on the open market, with the intention of buying them back later at a lower price to return to the lender. The difference between the sell and repurchase prices (minus fees and interest) is the trader’s profit. Whilst potentially lucrative, short selling carries significant risk: if the stock price rises instead of falls, losses can be theoretically unlimited. This is because the stock price can in theory go to infinity. It's often used by hedge funds, traders, and sophisticated investors as a tool for speculation or to hedge long positions.

Using put options is a more controlled method of expressing a bearish view, as the downside is limited to the premium paid.

Final Thoughts

Whilst derivatives offer powerful tools for managing risk and enhancing returns, they are generally not advised for most retail investors. The complexity of instruments such as options, futures, and swaps, combined with the potential for significant losses due to leverage, time decay, and volatility misjudgement, makes them unsuitable for individuals lacking technical knowledge or risk management experience. Research shows that the majority of retail traders who engage in short-term options trading lose money, with consistent underperformance relative to passive strategies (Barber et al. 2021). Regulatory bodies such as the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have classified derivatives as complex instruments and require retail clients to pass appropriateness assessments before gaining access to them (FCA 2023). For the vast majority, a diversified portfolio of equities and bonds remains the most prudent and transparent approach for long-term wealth accumulation.

References

Barber, Brad M., Xing Huang, and Terrance Odean. 2021. ‘Retail Investor Trading in Options and the Rise of the Big Three Wholesalers’. Working Paper, UC Davis. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3774423

Black, Fischer, and Myron Scholes. 1973. ‘The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities’. Journal of Political Economy 81 (3): 637–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/260062

Culp, Christopher L. 2011. Risk Transfer: Derivatives in Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Duffie, Darrell, and Haoxiang Zhu. 2011. ‘Does a Central Clearing Counterparty Reduce Counterparty Risk?’ Review of Asset Pricing Studies 1 (1): 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/rapstu/rar001

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). 2023. ‘Policy Statement PS23/3: Improving Outcomes for Consumers in High-Risk Investment Markets’. https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/policy-statements/ps23-3

Hull, John C. 2022. Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives. 11th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Stulz, René M. 2004. ‘Should We Fear Derivatives?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 18 (3): 173–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330042162360