Featured and Latest Posts

The Value Premium: Why ‘Cheap’ Stocks Have Tended to Win Long-term, but Why the Premium Often Feels ‘Dead’

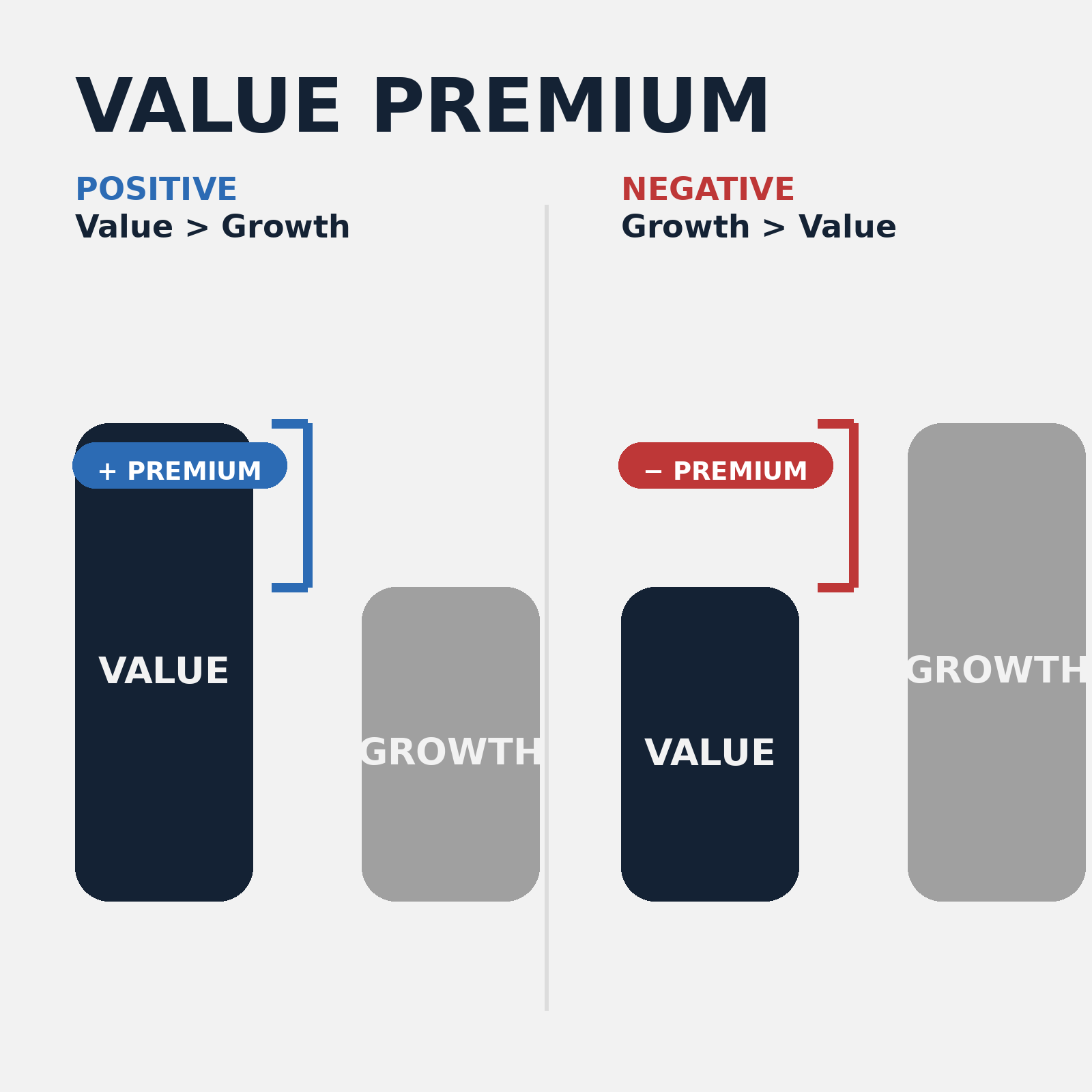

Value is the tendency for cheap stocks, those trading on low valuations relative to fundamentals, to outperform expensive growth stocks over the long run. In the factor investing world, value is not a story first and a regression second. It is a portfolio idea: own the cheaper end of the market and underweight the priciest end, then accept the return pattern that comes with that positioning.

And that return pattern is the whole point. Value’s history is lumpy, with long stretches where it looks broken, followed by sharp recoveries that often arrive after investors have lost patience. That is why value is so hard to hold, because it can feel like you are wrong for years. Ironically, this is also why it can persist, either because it is genuinely riskier in the bad economic states that many investors fear, or because investors repeatedly overpay for glamour and underpay for dullness until expectations mean revert.

How Fama and French Build Portfolios

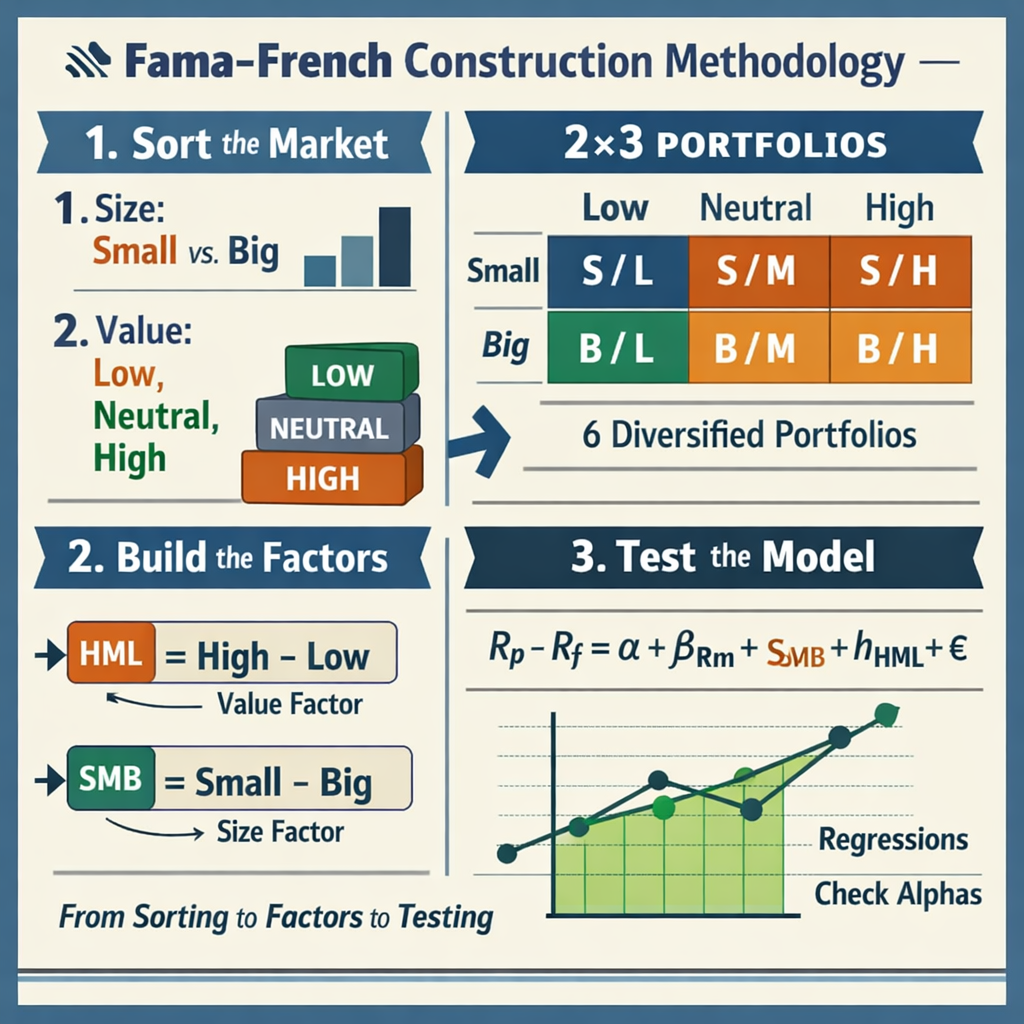

The Fama–French models begin with portfolio construction, not regressions. The idea is to sort stocks on characteristics thought to be related to expected returns, form a small number of broad and diversified portfolios, and then study how average returns vary across those portfolios. The familiar factors are built directly from these same sorts, which is why the approach is so transparent and replicable. A simple 2×3 sort, for example, splits stocks into Small and Big, then into Low, Neutral, and High on a second characteristic, producing six portfolios whose return patterns act as a clean diagnostic.

Once the portfolios are formed, factor construction and testing are deliberately mechanical. Long–short factors compare High versus Low or Small versus Big whilst averaging across the independent variable to control for it. When more detail is needed, the same logic scales up to 5×5 sorts, producing 25 portfolios that show whether return patterns are smooth and monotonic rather than driven by a single breakpoint. These portfolios then serve as test assets in regressions, where the key question is whether factor exposures explain the differences in average returns between the portfolios created by the sorts, leaving little systematic alpha behind.

Sharpe’s Arithmetic, Revisited: When ‘Average Active’ Might Beat ‘Average Passive’ Before Costs

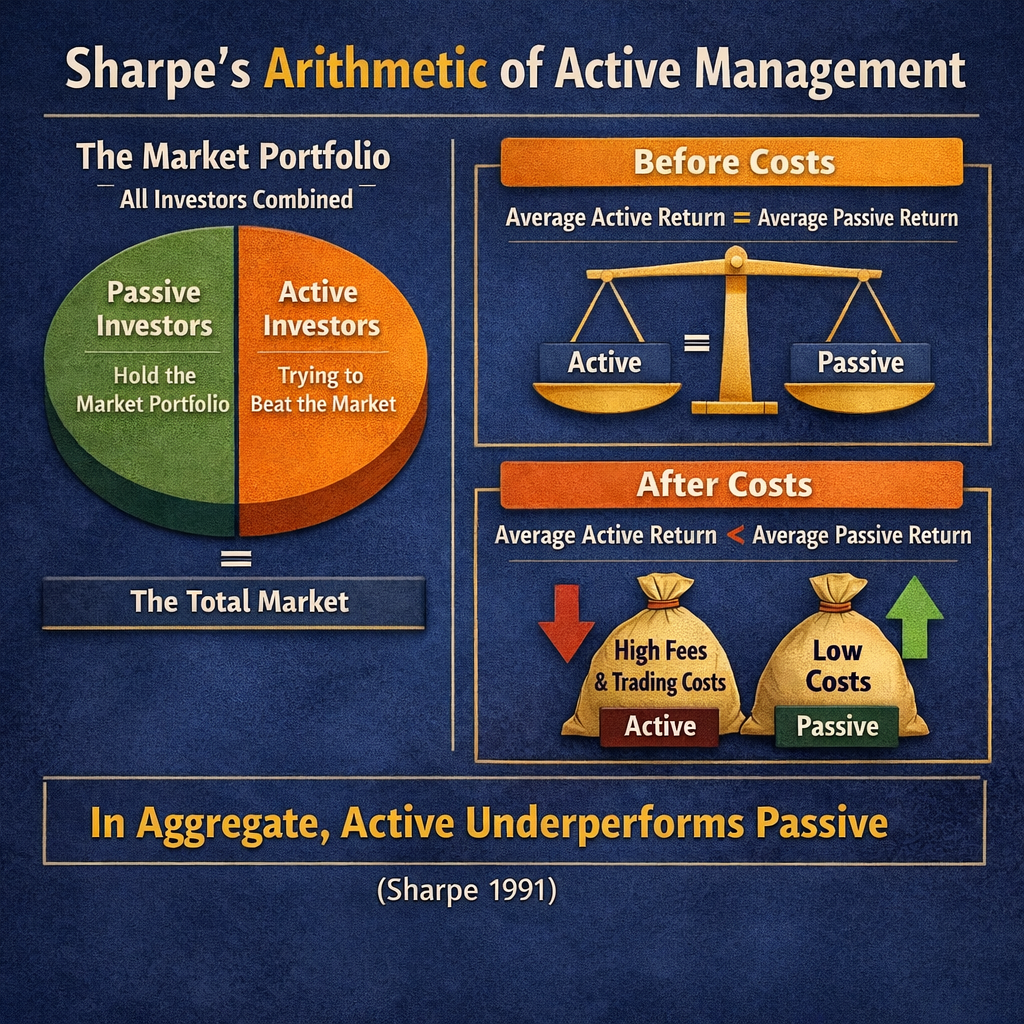

Sharpe’s ‘Arithmetic of Active Management’ is powerful because it is an accounting identity, not a claim about skill. If passive investors hold the market portfolio, then everyone else, collectively, must hold the same market portfolio too. That means, before costs, the average actively managed pound must earn the same return as the average passively managed pound. After costs, active underperforms in aggregate because it bears higher fees, turnover, and trading frictions.

The wrinkle is that the market portfolio is not static, and passive implementation is not continuous. Corporate actions reshape the investable set, whilst index trackers rebalance on rules and schedules, creating brief mismatches with the ‘instantaneous’ market. In that more realistic setting, average active can slightly outperform average passive before costs by intermediating those flows, without any special forecasting skill. But competition and costs still mean the core practical conclusion remains: passive tends to win after fees.

The Main Components of Bond Returns: Carry, Roll-down, and the Yield-curve Surprise

Bond returns can look deceptively simple: you lend money to a government or company, collect coupons, and get your principal back at maturity. The surprise is that, over short periods, even ‘safe’ bonds can fall sharply in value whilst still paying those coupons. That is not a glitch, it is just the market repricing what interest rates should be, and bond prices adjusting immediately.

A helpful way to think about it is that a bond’s return has three moving parts: what you get paid for holding it (carry), what you might gain simply because time passes on a normally upwards-sloping yield curve (roll-down), and the unpredictable bit (the yield-curve surprise). Carry and roll-down are the ‘expected’ components implied by today’s pricing. The surprise is ‘what the yield curve actually does’, and it can easily overwhelm the first two when interest rates change quickly.

Good financial decisions aren’t about predicting the future, they’re about following a sound process today.

In investing, outcomes are noisy. Short-term performance often reflects randomness, not skill. Yet fund managers continue to pitch five-year track records as if they prove anything. They don’t.

As Ken French puts it, a five-year chart ‘tells you nothing’. The real skill lies in filtering out the noise, evaluating strategy, incentives, costs, and behavioural fit.

Don’t chase what worked recently. Stick with what works reliably.