Why Picking Individual Stocks Is Not a Good Idea

Stock picking has long been romanticised as a way to grow wealth and beat the market. From Warren Buffett anecdotes to Reddit-fuelled stock-picking mania, the idea of selecting a few winning companies appeals to many investors. But for most people, this strategy is not only ineffective, it’s risky, inefficient, and statistically unlikely to succeed.

Here’s why picking individual stocks is usually a losing game.

Excess Idiosyncratic Risk

When you invest in just a handful of companies, you expose your portfolio to idiosyncratic risk (also known as non-systematic risk), the risk unique to a specific business. This includes factors such as:

A management scandal.

Regulatory fines.

Product recalls.

Loss of key customers.

Poor earnings results.

This kind of risk is unpredictable and specific to the company in question. Unlike broad economic risk (known as systematic risk), idiosyncratic risk can be diversified away and therefore, investors are not compensated for bearing it (Markowitz 1952).

The Mathematics of Diversification

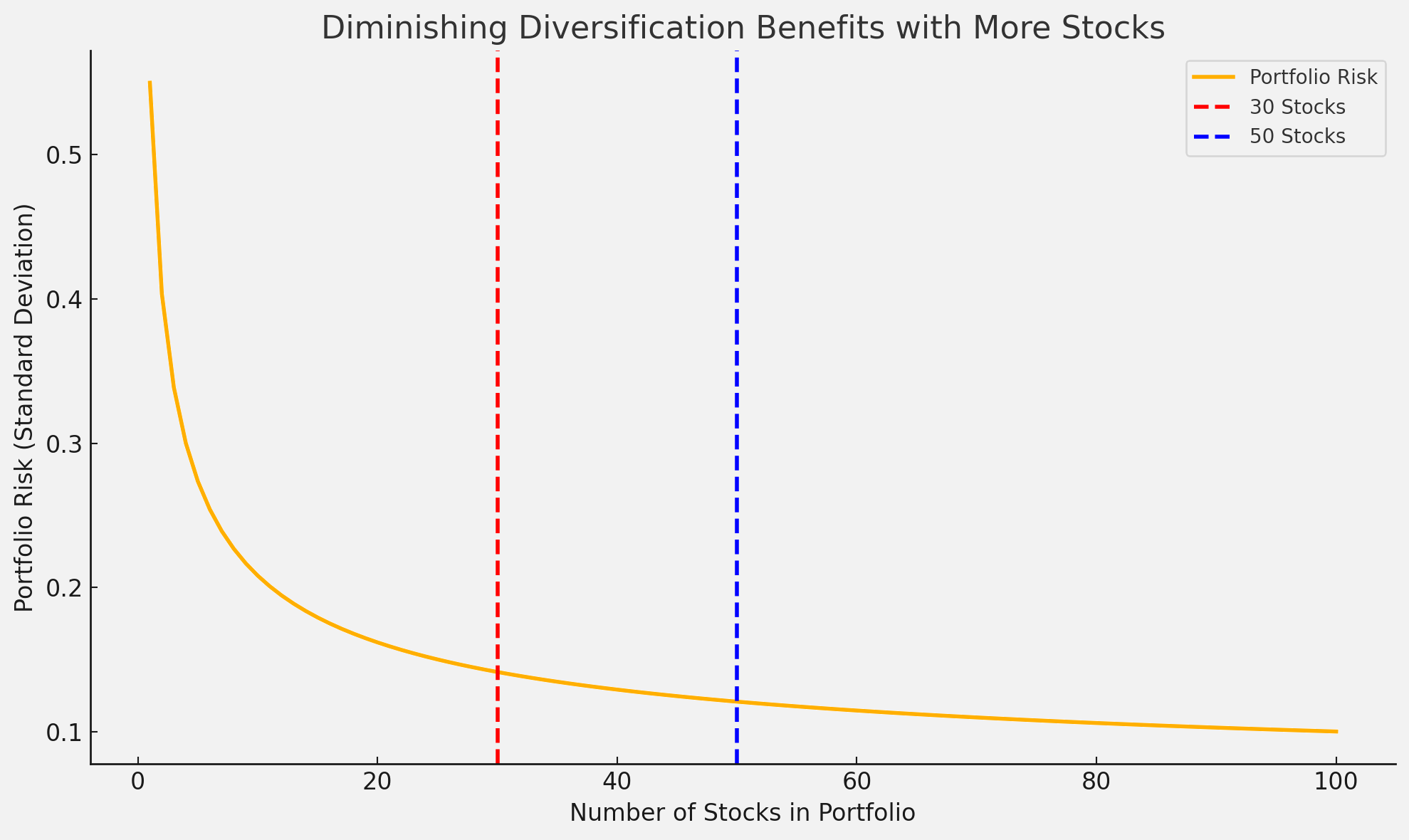

Research shows that a portfolio of around 20 to 30 well-selected stocks across different industries and regions eliminates over 90% of idiosyncratic risk (Statman 1987). Yet many retail investors pick only 5 to 10 stocks, leaving themselves exposed to avoidable volatility and unrewarded risk.

A Real-World Example: Wirecard AG

Consider Wirecard AG, the German fintech company once hailed as Europe’s answer to PayPal. At its peak in 2018, it was worth over €24 billion and had been added to the prestigious DAX 30 index. But in 2020, it collapsed into insolvency after a €1.9 billion hole was discovered in its accounts, one of the largest corporate frauds in German history.

Investors who held Wirecard as a large percentage of their portfolio, saw a total loss in that position. This would have decimated their returns.

By contrast, those who were invested in diversified funds such as the MSCI World fund barely noticed. Wirecard represented just 0.04% of the index at its peak, an insignificant amount.

This illustrates the core point: individual stock pickers accept higher volatility without any additional expected return, a poor trade-off for anyone seeking long-term growth.

Figure 1. Portfolio risk reduces significantly up to around 30–50 stocks, after which the benefits of diversification diminish rapidly. Data adapted from Evans and Archer (1968).

The Odds Are Against You

The most striking evidence against stock picking comes from the research of Hendrik Bessembinder. His studies reveal just how rare it is for a stock to outperform the market over time.

In the U.S. market, from 1926 to 2016, just 4% of stocks accounted for all net wealth creation. The rest underperformed cash or were outright failures (Bessembinder 2018). Let’s re-iterate. A tiny minority of companies (stocks) generate the majority of long-term gains. But the difficulty lies not in recognising them retrospectively, but in identifying them before they take off.

These high-performing companies are often indistinguishable early on from thousands of others with similar fundamentals or growth stories.

Many outperformers experience large drawdowns or years of flat returns before breaking out — making them hard to hold onto even if you did pick them.

Meanwhile, many companies with strong narratives and analyst support never deliver on their promise.

When expanded globally, the pattern is similar. Between 1990 and 2018, less than 1.3% of global stocks accounted for all net global stock market wealth creation (Bessembinder et al. 2020).

In short: the overwhelming majority of stocks fail to outperform broad indices, and only a tiny sliver of companies deliver the outsized gains that drive market returns. If you're picking individual stocks, you're effectively betting on finding that rare outperform and the odds are stacked against you.

Figure 2. The chart visualises global stock return outcomes, based on data from Bessembinder et al. (2020). It reveals the extreme skew in stock market performance:

The vast majority of individual stocks, shown under the large curve, underperformed U.S. Treasury bills or were complete failures.

Only 1.3% of global stocks (represented by the small orange bar on the far right) were responsible for all the net wealth creation in global equity markets over the 1990–2018 period.

The odds of selecting one of the rare winners are extremely low. Diversification is not just helpful, it’s essential to capture the upside of these few value-creating stocks while protecting against the downside of the many that disappoint.

The Analyst Illusion: Strong Buys That Strongly Crashed

History is littered with examples of seemingly promising stock picks that turned into disasters. Research from Bloomberg (2017) and J.P. Morgan Asset Management (2014) offers a sobering reminder: even stocks rated as ‘strong buys’ by professional analysts often fail to deliver. In fact, the Bloomberg study found that a significant portion of analyst-recommended stocks suffered steep price declines, with many losing over 50% of their value within a year. Similarly, J.P. Morgan’s research showed that from 1980 to 2014, nearly 40% of all stocks in the Russell 3000 experienced a catastrophic loss—defined as a 70% drop from peak value with little recovery. These findings highlight the asymmetric risk investors face when betting on individual companies, no matter how compelling the narrative or how confident the analyst.

Behavioural Pitfalls

Even if you do your homework, investors are still human and humans are prone to emotional decision-making that undermines long-term results. Some common behavioural pitfalls include:

Loss aversion: the tendency to feel the pain of losses more acutely than the pleasure of equivalent gains, leading to poor sell decisions or an aversion to rebalancing.

Overconfidence: overestimating one's ability to pick winners or time the market.

Recency bias: placing too much emphasis on recent performance when evaluating stocks, often chasing past winners.

Confirmation bias: seeking out only information that supports your thesis, while ignoring contradictory evidence.

Herding: following popular trends or tips without independent analysis.

Mental accounting: treating different pots of money differently, leading to inconsistent decision-making.

These biases lead to costly mistakes, such as buying high, selling low, or holding onto poor performers out of hope rather than logic. Passive investing strategies help avoid these errors by enforcing discipline and removing the need for constant decision-making.

Tax and Cost Inefficiency

Frequent buying and selling of individual shares can also lead to:

Higher transaction costs.

Greater bid-ask spreads.

Short-term capital gains tax liabilities (at higher rates than long-term gains in many jurisdictions).

Even if you manage to pick a few winning stocks, these frictions can quietly drag down your net returns over time.

The Better Alternative: Broad Diversification

Investing in a globally diversified, low-cost index fund helps you:

Avoid uncompensated idiosyncratic risk.

Maximise your exposure to the global growth engine.

Minimise behavioural mistakes and tax inefficiencies.

Match or likely beat the performance of most professional active managers (S&P Dow Jones Indices 2024).

You no longer need to bet on a few companies when you can own the market for a fraction of a percent in annual fees.

Final Thoughts

Picking individual stocks can work but only if you can consistently identify the rare winners, avoid behavioural traps, and manage risk better than most professionals. Extremely unlikely.

The rational approach is not to try to outguess the market, but to own as much of it as possible, stay diversified, and be patient.

Over time, this simple strategy wins more often than not.

References

Bessembinder, Hendrik. 2018. ‘Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?’ Journal of Financial Economics 129(3): 440–457.

Bessembinder, Hendrik, Te-Feng Chen, Goeun Choi, and K.C. John Wei. 2020. ‘Do Global Stocks Outperform US Treasury Bills?’ SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3536265.

Bloomberg. 2017. Analyst Recommendations Are Often Disastrously Wrong. Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-23/analyst-strong-buy-calls-can-lead-to-spectacular-losses

Evans, John L., and Stephen H. Archer. 1968. ‘Diversification and the Reduction of Dispersion: An Empirical Analysis’. The Journal of Finance 23 (5): 761–767. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325312

J.P. Morgan Asset Management. 2014. The Agony & The Ecstasy: The Risks and Rewards of a Concentrated Stock Position. https://am.jpmorgan.com/content/dam/jpm-am-aem/global/en/insights/portfolio-insights/mi-the-agony-and-the-ecstasy.pdf

Markowitz, Harry. 1952. ‘Portfolio Selection’. The Journal of Finance 7(1): 77–91.

S&P Dow Jones Indices. 2024. SPIVA® U.S. Scorecard Year-End 2023.

Statman, Meir. 1987. ‘How Many Stocks Make a Diversified Portfolio?’ Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 22(3): 353–363.