Featured and Latest Posts

Inflation Swaps In A Short-Duration Bond Fund

If you want UK inflation protection, the obvious route is index-linked gilts. The problem is that the linker market is relatively narrow and often pushes you into longer-duration exposure, so performance can end up being dominated by real-rate duration and price volatility rather than inflation protection. Dimensional’s design choice in the Sterling Short Duration Real Return Fund is to separate those moving parts: keep the bond portfolio short and diversified (including investment-grade credit), then attach inflation sensitivity via an overlay of UK RPI inflation swaps.

That is the key idea: a physical linker bundles inflation linkage with real-rate duration, whereas a swap overlay lets you target inflation exposure without being forced into long duration. The fund is not risk free. Credit spreads can widen, and implementation frictions matter, but the risk mix is different from a linker-heavy approach.

An Assessment of an Equal Weighting Strategy

Market-cap weighted indices let prices set the portfolio weights, so the fund tracks the overall market closely. Equal weighting strategies give every stock the same weight, which is often pitched as a way to avoid ‘bubbles’. However, most of the difference is not magic outperformance. Indeed, it is a different, riskier set of exposures, especially towards smaller and cheaper companies.

Mechanically, equal weighting strategies underweight the biggest firms and overweight small names which results in frequent rebalancing to keep weights equal. That means higher turnover and trading costs, particularly in less liquid stocks. Equal weighting also tends to sell recent winners and buy recent losers, which can blunt upside participation and leave you more exposed to struggling businesses than a market-cap weighted index would.

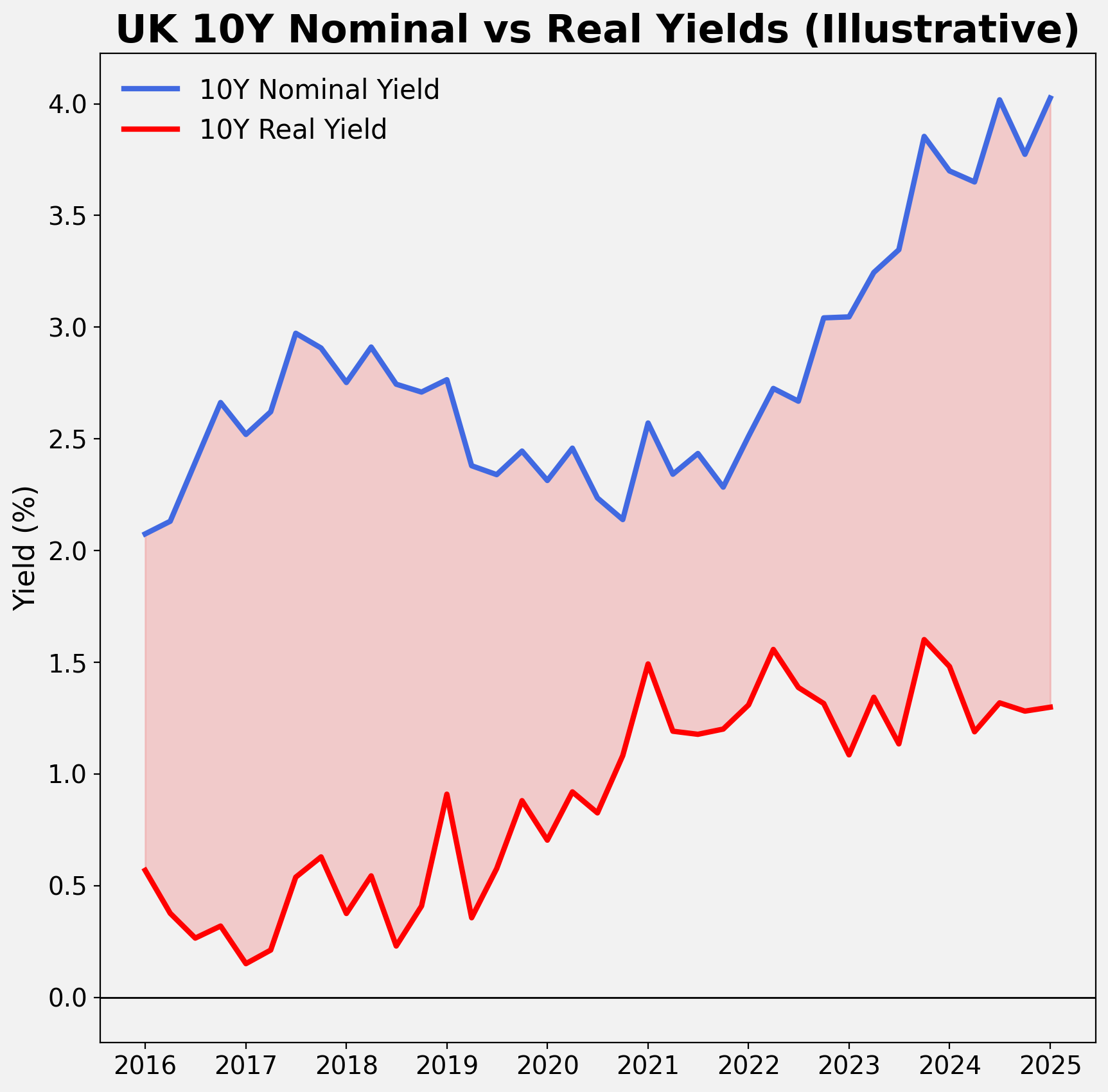

Nominal vs Real Yield Curves: Understanding Inflation Protection

Nominal and real yield curves often appear similar, which leads some investors to assume they say the same thing about interest rates and inflation. In reality, nominal gilt yields include compensation for inflation, whereas index-linked gilt yields are quoted after inflation has already been accounted for. The gap between the two, breakeven inflation, is not a clean read of future inflation because it also reflects liquidity conditions, the value placed on inflation protection and distortions in the index-linked market.

These differences matter for returns. Inflation-linked gilts provide inflation-adjusted cashflows, but their prices remain highly sensitive to changes in real yields. When real yields rise, they typically fall more sharply than equivalent nominal gilts, and any CPI uplift takes time to offset those losses. Inflation linkers work best when inflation risk increases more than expected, not merely when inflation is high. Understanding this distinction helps investors avoid disappointment and use inflation-linked gilts more effectively.

What Equity Returns Really Are

When people talk about ‘equity returns’, they often mean whatever percentage the market delivered last year. That is fine for storytelling, but it is not a definition. A cleaner starting point is price return versus total return: price return is just the change in the share price, whilst total return includes cashflows, typically assuming they are reinvested.

From there, returns can be broken into what must add up mechanically: shareholder yield, nominal earnings growth, and changes in valuation multiples. Yield is broader than dividends alone, because shareholders can also benefit from buybacks and sensible capital allocation, including debt reduction or reinvestment when expected ROIC is attractive. Valuation changes can dominate in the short run, but they are the least reliable piece to ‘count on’, which is why this decomposition keeps return expectations honest.

Good financial decisions aren’t about predicting the future, they’re about following a sound process today.

In investing, outcomes are noisy. Short-term performance often reflects randomness, not skill. Yet fund managers continue to pitch five-year track records as if they prove anything. They don’t.

As Ken French puts it, a five-year chart ‘tells you nothing’. The real skill lies in filtering out the noise, evaluating strategy, incentives, costs, and behavioural fit.

Don’t chase what worked recently. Stick with what works reliably.