Featured and Latest Posts

Short Rates Vs Long Rates: Why Central Banks Don’t Set Mortgage Rates

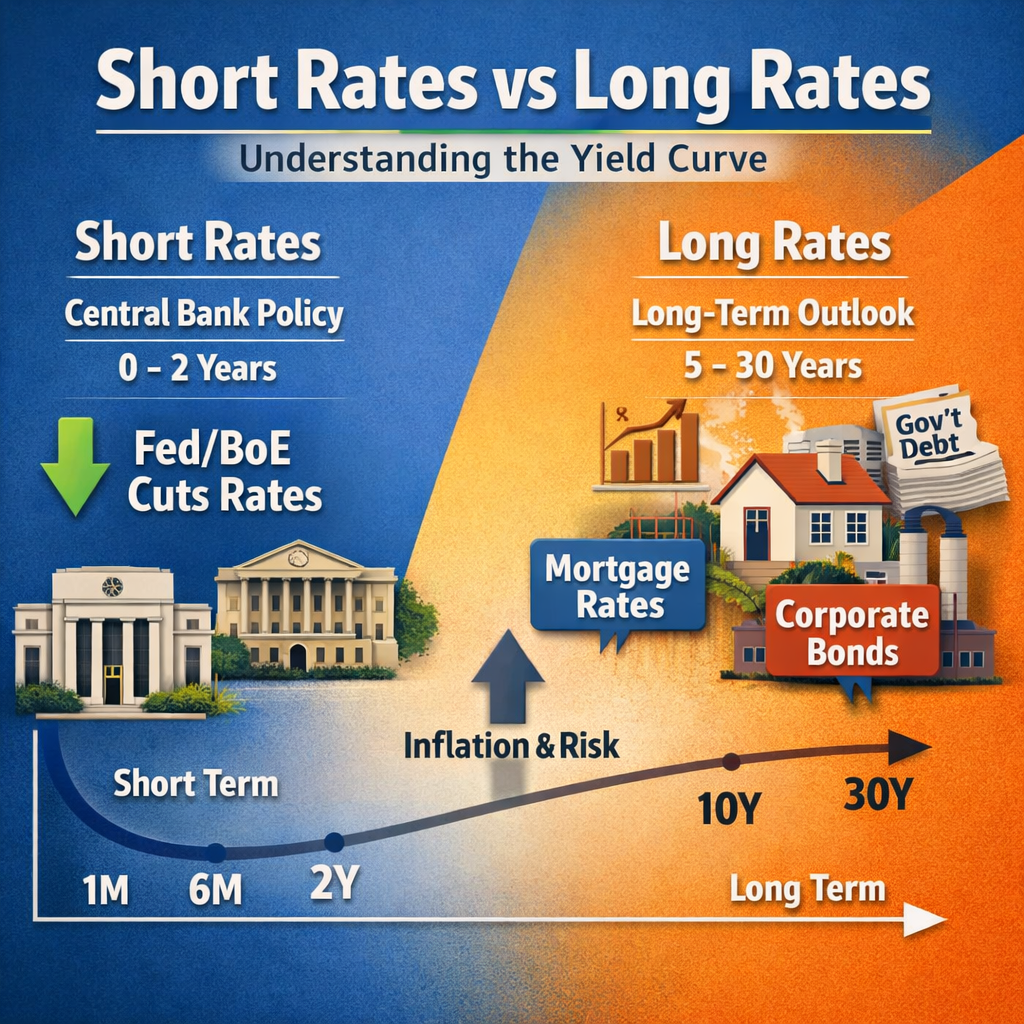

Short rates sit at the front end of the yield curve and mostly reflect what the central bank is doing now and what markets expect over the next year or two. Long rates are set by investors looking out over the next decade, so they reflect longer-run inflation and growth expectations plus extra compensation for uncertainty (the term premium). That’s why the Fed or Bank of England can cut rates whilst long yields barely move: markets may think the cuts won’t last, or they may demand a higher term premium. And because many fixed borrowing costs are priced off longer-term yields plus a spread, mortgages and corporate debt can stay expensive even as policy rates fall.

Quantitative Easing, Stablecoins, and Bitcoin’s Fixed Supply: Why Neither Crypto ‘Solution’ Fixes the Money Problem

Money supports a modern economy by enabling exchange, providing a unit of account and acting as a store of value. Fiat money works because it is backed by law, taxation and a central bank that stabilises the financial system. Most money is created by private banks when they make loans, and banks settle their net flows using reserves in the overnight market. Central banks guide the cost of this funding through open market operations, influencing borrowing conditions across the economy. When interest rates are near zero, they turn to quantitative easing, which creates reserves to buy longer-dated government and high-quality private assets in order to support liquidity and lower long-term rates. QE appeared profitable when rates were low but has since become costly as reserve remuneration has risen, yet its role in preventing financial collapse shows why a centralised banking system remains indispensable.

Crypto experiments test whether parts of this system can be replaced. Stablecoins depend on private issuers managing reserve portfolios without a public backstop, which makes their one-to-one promises vulnerable to runs when assets fall or liquidity dries up. Bitcoin avoids runs because it has no issuer and no redemption promise, but a fixed supply, high volatility and the lack of a lender of last resort mean it cannot meet the needs of a large, dynamic economy. Its long-term security also depends on transaction fees once block subsidy ends. Overall, these technologies cannot replicate the trust, elasticity and institutional support that make fiat money and centralised banking both stable and efficient.

When the Essentials Became a Luxury: The Rise of Intergenerational Inequality

Streaming, smartphones, and cheap flights make it easy to believe we’ve never had it so good. But beneath the surface, younger generations are struggling with something far more serious: the essentials have become unaffordable.

For Millennials and Gen Z, owning a home, raising a family, or saving for retirement is harder than it was for their parents—despite higher qualifications and greater workforce participation. Whilst consumer goods have become cheaper, the building blocks of a stable life have slipped further out of reach.

This post explores how that happened—and why the odds feel stacked against the young.

Good financial decisions aren’t about predicting the future, they’re about following a sound process today.

In investing, outcomes are noisy. Short-term performance often reflects randomness, not skill. Yet fund managers continue to pitch five-year track records as if they prove anything. They don’t.

As Ken French puts it, a five-year chart ‘tells you nothing’. The real skill lies in filtering out the noise, evaluating strategy, incentives, costs, and behavioural fit.

Don’t chase what worked recently. Stick with what works reliably.