Featured and Latest Posts

High Yields, Hidden Risks: Why Structured Products Favour the Seller

Structured products promise the best of both worlds: stock market upside with limited downside. It’s a compelling pitch, especially in uncertain markets. But beneath the glossy brochures and bespoke payoffs lies a very different story—one where complexity conceals cost, and the bank always wins. These instruments are engineered using a mix of bonds and derivatives, allowing issuers to extract profit through hidden margins and asymmetric risk. Investors are often unknowingly writing options, capping their upside whilst absorbing significant downside risk. As multiple studies show, the expected returns on structured notes are frequently negative once fees and structural constraints are accounted for. For most retail investors, the allure of structured products is an expensive mirage—cleverly designed to benefit the issuer far more than the investor.

Understanding Derivatives: Risks and Rewards

Derivatives are financial contracts whose value is linked to the performance of an underlying asset, index, or rate. Used for hedging, speculation, or market access, they include instruments like futures, forwards, options, and swaps. Futures and forwards lock in prices for future transactions, whilst options grant rights to buy or sell without obligation—offering strategic flexibility. These instruments are traded either on regulated exchanges or over-the-counter, with pricing influenced by factors such as interest rates, income flows, and storage costs. Though derivatives can be powerful tools, they come with complex risk–reward profiles that demand careful understanding.

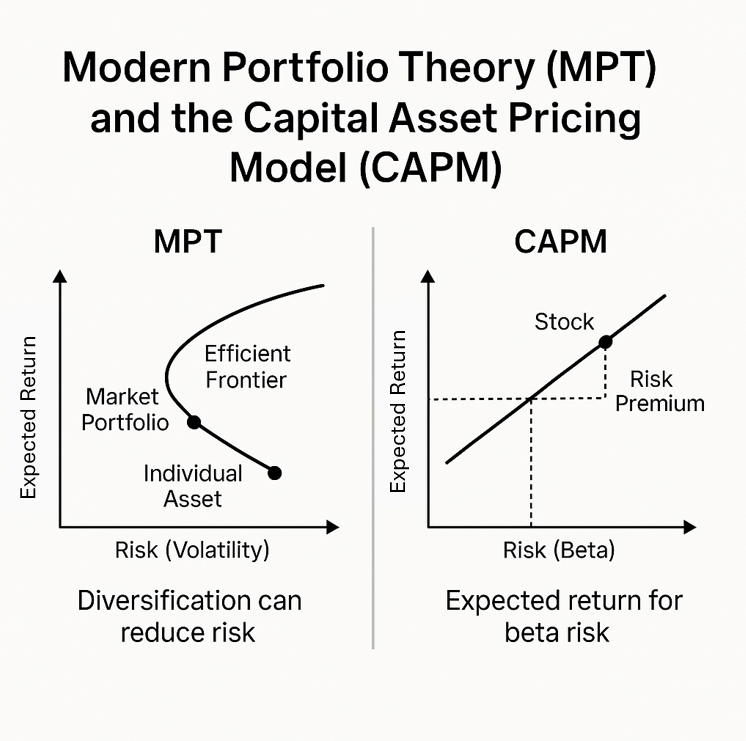

The Foundations of Modern Investing: Why Markowitz and the CAPM Still Matter

Ever wondered how investors decide what a fair return is for taking on risk? Two foundational ideas—Modern Portfolio Theory and the Capital Asset Pricing Model—help explain it. Markowitz shows that smart investing is about how assets work together, not just about how they perform alone. Sharpe built on this by arguing that only market-wide risk (not company-specific risk) should earn investors a return. These theories still shape how portfolios are built today.

Beyond the Three-Factor Model: RAFI, Profitability and the Evolution of Smart Beta

The Fama-French Three-Factor Model (1993) was a milestone in modern finance, offering a more complete explanation of asset returns by introducing size and value alongside market beta. Yet even this expanded framework struggled with persistent anomalies—such as the underperformance of value stocks as defined by the price-to-book ratio, and the puzzling momentum premium.

In this article, we examine how two complementary innovations—RAFI’s Fundamental Indexing and Robert Novy-Marx’s profitability factor—have sharpened the lens through which we view value investing. Each, in its own way, addresses the limitations of traditional value definitions and helps distinguish true bargains from value traps. We also explore the role of momentum in asset pricing and why Fama and French, despite acknowledging its power, ultimately excluded it from their Five-Factor Model (2015).

Together, these ideas illustrate that the future of value investing may lie not in abandoning it, but in redefining how we measure it.

Good financial decisions aren’t about predicting the future, they’re about following a sound process today.

In investing, outcomes are noisy. Short-term performance often reflects randomness, not skill. Yet fund managers continue to pitch five-year track records as if they prove anything. They don’t.

As Ken French puts it, a five-year chart ‘tells you nothing’. The real skill lies in filtering out the noise, evaluating strategy, incentives, costs, and behavioural fit.

Don’t chase what worked recently. Stick with what works reliably.