Featured and Latest Posts

What Equity Returns Really Are

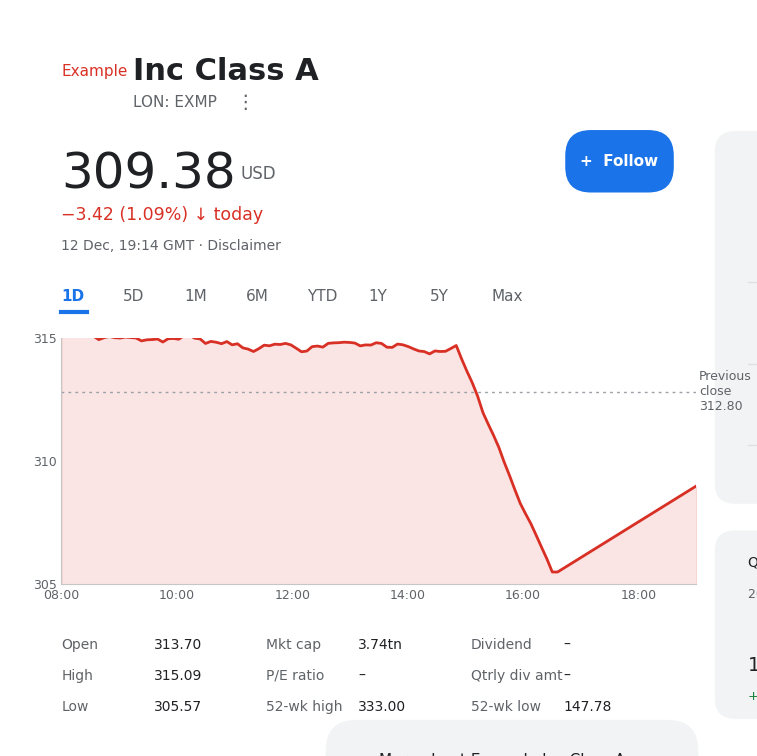

When people talk about ‘equity returns’, they often mean whatever percentage the market delivered last year. That is fine for storytelling, but it is not a definition. A cleaner starting point is price return versus total return: price return is just the change in the share price, whilst total return includes cashflows, typically assuming they are reinvested.

From there, returns can be broken into what must add up mechanically: shareholder yield, nominal earnings growth, and changes in valuation multiples. Yield is broader than dividends alone, because shareholders can also benefit from buybacks and sensible capital allocation, including debt reduction or reinvestment when expected ROIC is attractive. Valuation changes can dominate in the short run, but they are the least reliable piece to ‘count on’, which is why this decomposition keeps return expectations honest.

Cash, Accruals, Intangibles and Sector Effects: What Really Separates Avantis and Dimensional?

Avantis and Dimensional are often grouped together for good reason. Both sit firmly within the evidence-based investing tradition, draw heavily on the academic asset-pricing literature, and reject discretionary stock picking in favour of systematic exposure to well-documented sources of expected return. That shared philosophy is no accident. Avantis was founded by former Dimensional professionals and reflects the same intellectual lineage: factor investing grounded in theory, long-run evidence and practical implementability.

Where the firms differ is not in ideology, but in execution. The key distinctions centre on how accounting data are interpreted and adjusted when constructing value and profitability signals. In particular, two related but distinct debates drive much of the divergence: how profitability should be measured, especially whether earnings should be adjusted to be more cash-like by stripping out accruals, and how book equity should be defined in an economy dominated by intangible assets. Together, these design choices explain much of the subtle but meaningful difference between Avantis and Dimensional, differences that ultimately reflect alternative trade-offs between accounting precision and robustness rather than fundamentally different views on markets.

The Total Costs of Investing

Investors often focus on the headline fee of a fund whilst overlooking the many other frictions that quietly erode returns. The Ongoing Charges Figure is only the starting point. Trading and transaction costs, platform fees, taxes, spreads, incentive structures and even investor behaviour all contribute to the true cost of ownership. Some of these costs are explicit and easy to measure, whilst others are embedded within performance and only reveal themselves over time. Understanding this wider cost ecosystem allows investors to minimise unnecessary frictions, pay consciously for genuine value and keep a greater share of the capital markets’ long term rewards.

Quantitative Easing, Stablecoins, and Bitcoin’s Fixed Supply: Why Neither Crypto ‘Solution’ Fixes the Money Problem

Money supports a modern economy by enabling exchange, providing a unit of account and acting as a store of value. Fiat money works because it is backed by law, taxation and a central bank that stabilises the financial system. Most money is created by private banks when they make loans, and banks settle their net flows using reserves in the overnight market. Central banks guide the cost of this funding through open market operations, influencing borrowing conditions across the economy. When interest rates are near zero, they turn to quantitative easing, which creates reserves to buy longer-dated government and high-quality private assets in order to support liquidity and lower long-term rates. QE appeared profitable when rates were low but has since become costly as reserve remuneration has risen, yet its role in preventing financial collapse shows why a centralised banking system remains indispensable.

Crypto experiments test whether parts of this system can be replaced. Stablecoins depend on private issuers managing reserve portfolios without a public backstop, which makes their one-to-one promises vulnerable to runs when assets fall or liquidity dries up. Bitcoin avoids runs because it has no issuer and no redemption promise, but a fixed supply, high volatility and the lack of a lender of last resort mean it cannot meet the needs of a large, dynamic economy. Its long-term security also depends on transaction fees once block subsidy ends. Overall, these technologies cannot replicate the trust, elasticity and institutional support that make fiat money and centralised banking both stable and efficient.

Good financial decisions aren’t about predicting the future, they’re about following a sound process today.

In investing, outcomes are noisy. Short-term performance often reflects randomness, not skill. Yet fund managers continue to pitch five-year track records as if they prove anything. They don’t.

As Ken French puts it, a five-year chart ‘tells you nothing’. The real skill lies in filtering out the noise, evaluating strategy, incentives, costs, and behavioural fit.

Don’t chase what worked recently. Stick with what works reliably.